Robotics 1: 315P

For much of the Over Under and High Stakes seasons of the VEX V5 Robotics Competition, I served as the lead coder for the middle school team 315P. This post is a collection of my thoughts about working on it :) I might be writing a sequel to this in the coming months about my continued journey with robotics.

Season 1: Over Under

Note from 2025: The following is an unedited copy of a blog post, titled “My Experience Playing in the VEX V5 Robotics Competition” I wrote about my time on the team during Over Under. It was written at the behest of my coach during the beginning of the summer of 2024. 🚨CRINGE ALERT🚨

The VEX V5 Robotics Competition (V5RC) is a student-centered robotics program which educates teams on crucial skills and techniques. The game for the 2023-2024 season was called Over Under. This article is about my experience playing Over Under as part of the team 315P.

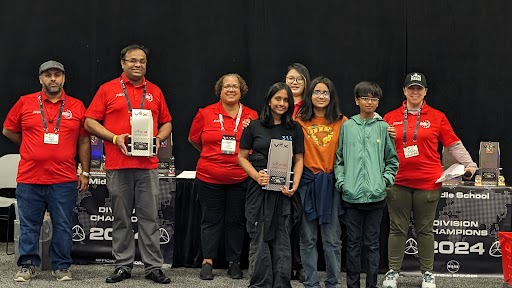

The team receiving the Amaze Award at the world championships. From left to right: Sanvi, Dyuthi, Aadish.

The team receiving the Amaze Award at the world championships. From left to right: Sanvi, Dyuthi, Aadish.

The Game

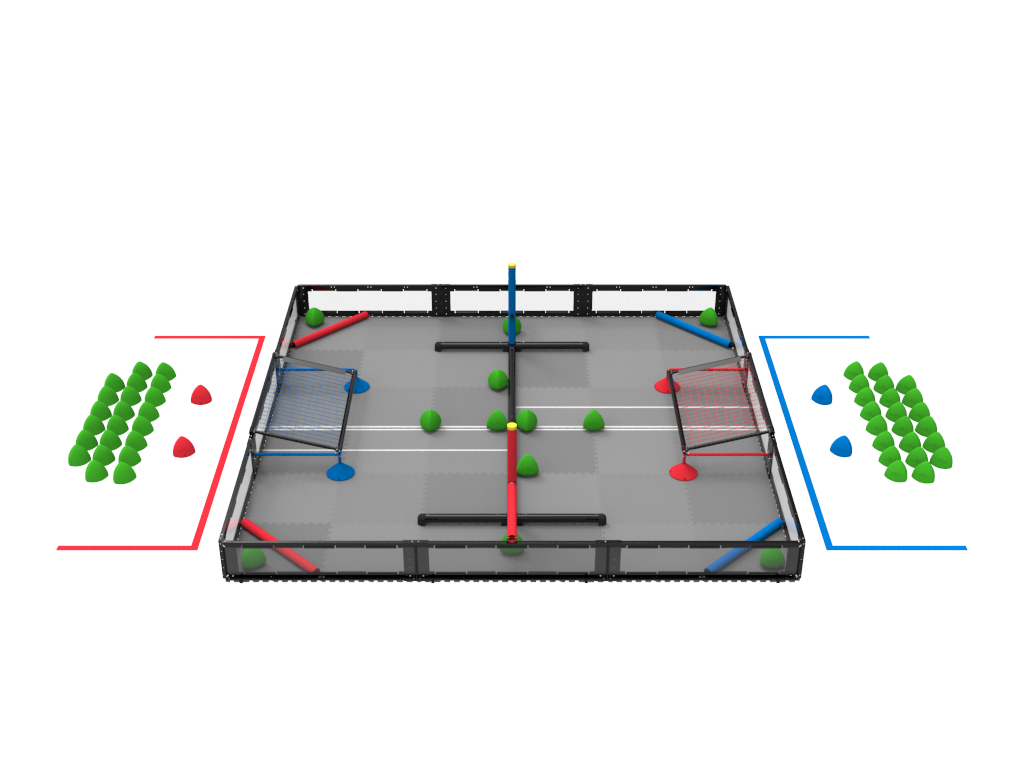

The V5RC Over Under match field.

The V5RC Over Under match field.

Over Under is a soccer-like game, played by two competing alliances (an alliance consists of two teams, each of which builds and competes with one robot) There is a central barrier dividing the field (whose ground is made of foam tiles) into two halves; each half contains a goal to score oddly-shaped triballs in. Each game starts with a few trials on the field and team members can introduce triballs onto a robot under certain conditions (this is called match loading). There are two alliance-specific climbing locations where robots can elevate themselves on poles in the last few seconds of the match to earn a climbing bonus. A match consists of a 15-second autonomous period where robots move on their own and a 1 minute, 45 second driver controlled period.

Teams can compete in tournaments, in which they play numerous games against other teams. The best performing team at a tournament is crowned tournament champion. By creating an engineering notebook (which details a team’s design process for their robot) and completing an interview, teams also have the opportunity to win various judge’s awards.

Finally, robots can also participate in skills challenges, in which only one robot is on the field (in contrast with the four robots of regular matches) and has one minute to score as highly as possible. The team at a tournament with the highest skills score is crowned skills champion.

The Team

I was lucky to be part of team 315P, a member of the Paradigm club. Paradigm is an organization of teams in Northern California; all Paradigm teams have team numbers that start with 315. Member teams of Paradigm help out, practice with, and provide parts to one another. 315P is one of Paradigm’s four middle school teams. (V5RC is mostly centered around the high school division, but there are also many middle school teams. There are around 40% less middle school teams.) During Over Under, 315P was a three-person team (including me). I am extremely fortunate to have been able to join mid-season, which is very uncommon amongst V5RC teams. Every member had important designated roles:

- Sanvi, the driver. Sanvi designed and guided our robot build, and contributed the most towards the hardware. She was in charge of every component except the catapult, and often put in a lot of extra work to earn top-tier driver skills.

- Dyuthi, the strategist. Dyuthi partially coded some of the team’s autonomous routines and built and maintained our fabulous catapult. She also worked hand-in-hand with Sanvi to analyze dozens of our past matches before every tournament, allowing the team to develop a dynamic and high-performance game strategy.

- And I, Aadish, a coder. I developed the core autonomous architecture and many of the team’s autonomous programs. I also communicated with our alliance during and before matches; this was a key method the team used to maximize our synergy with alliance partners.

Overall, each team member had an important role in the team, custom-fit for our ability while also teaching us various life skills. These roles, of course, were not set in stone; it would be a common occurrence to see an all-team discussion on various important aspects of our strategy, from the motions of the robot to size of a component.

The Robot & Strategy

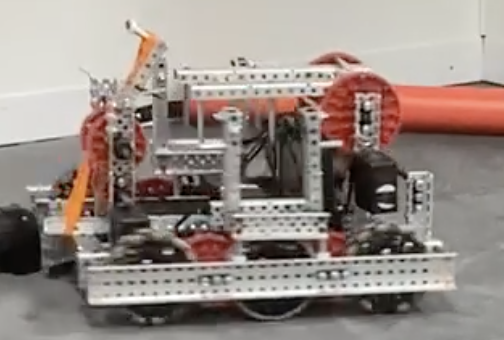

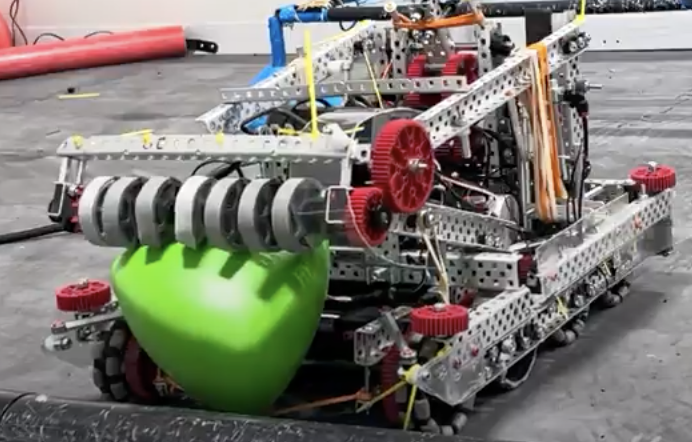

Above: our robot, Friday

The initial “meta” strategy (a meta in robotics is used to describe a trend) was to build a high-performance catapult, which could then shoot triballs over the barrier. There, an alliance partner’s robot could easily sweep triballs into the goal. In order to do this, we built our second robot, named Friday. (I wasn’t there to witness our first robot, Jarvis.) Friday was a simple robot, with a drivetrain that was fairly slow but high-torque, a claw-style intake to hold triballs, a slow but reliable catapult, one set of pneumatic “wings” to push multiple triballs at once, and a motor-powered climb mechanism.

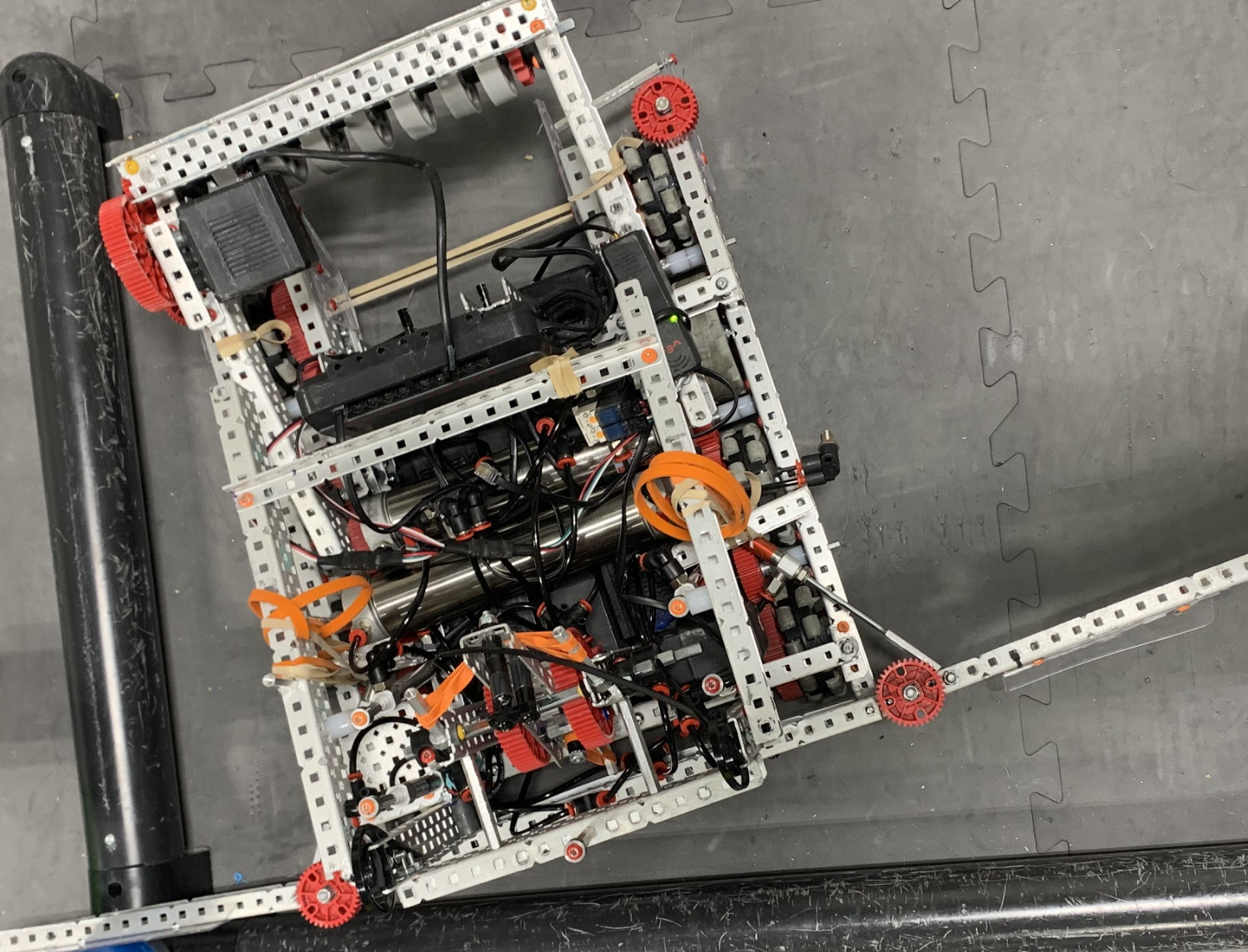

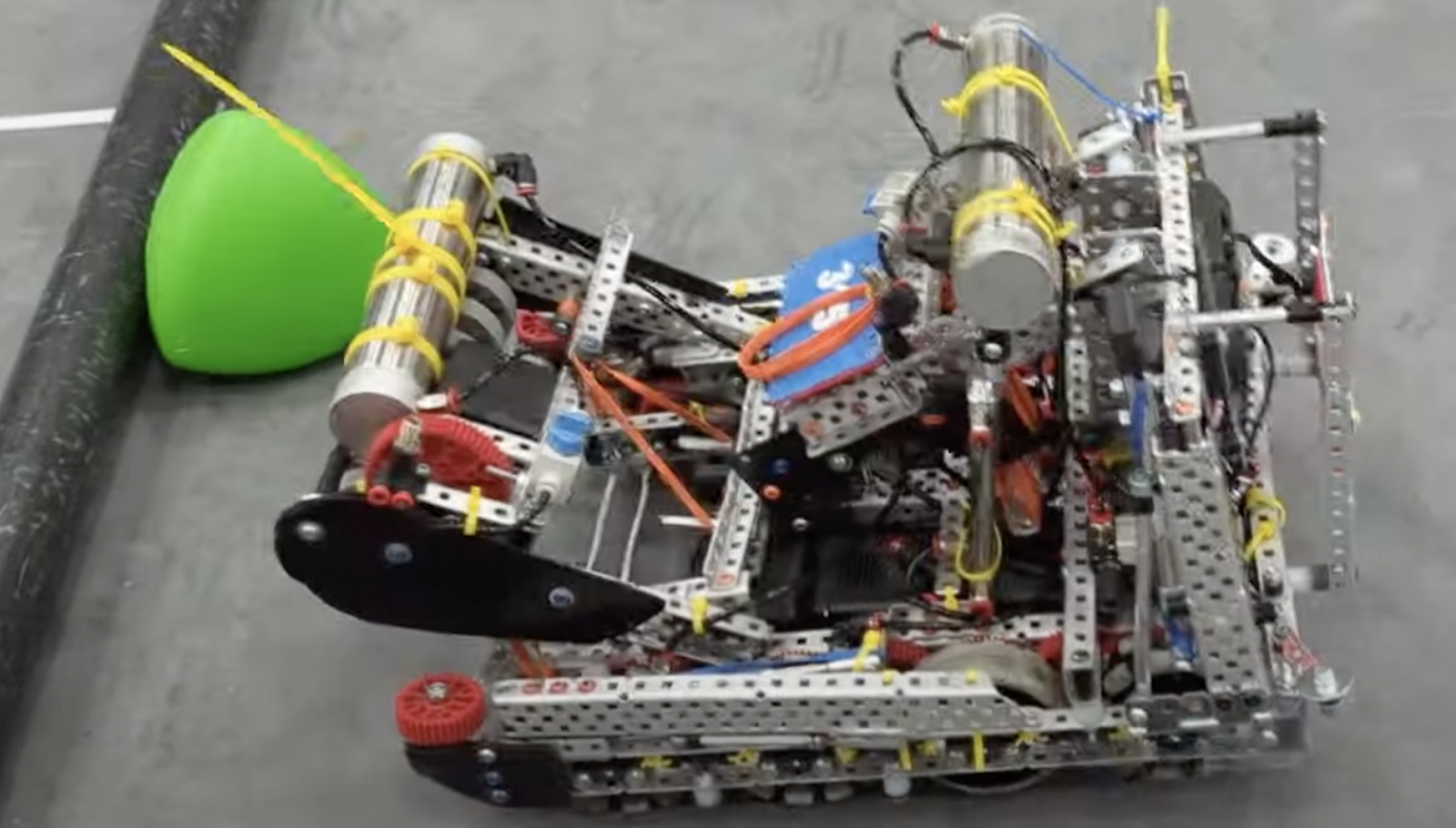

Above two pictures: our robot, Marvin

Above two pictures: our robot, Marvin

Eventually, though, the game became more defensive. Some smart cookie somewhere realized that with specially shaped wings, robots could easily push over and score triballs catapulted by the opponent alliance. This strategy initiated the rise of robots which, like leeches, stole opponents’ triballs instead of introducing their own. In order to avoid such effective strategies, triball control became the name of the game. This evolved into two main meta strategies. The first is one-by-ones, in which a single triball is placed into a robot’s intake; then, the robot drives over or around the barrier to score it. One-by-ones are almost completely resistant to defense (only inferior to specialized robots which are designed to steal triballs from intakes), but fairly slow in scoring. The second strategy is bowling, in which numerous triballs are placed in front of a robot, which then drives around the barrier to push all of them into the goal. Bowling can easily score one hundred points in a minute, but is more prone to getting disrupted by defense. Most teams, including us, used a combination of the two, in which the strategist makes a choice about which strategy to use based on the state of the match. In order to facilitate this change in game strategy, we built our second robot, Marvin. Marvin maintained the same drivetrain, but added two motors to improve torque (the number of motors doesn’t impact speed). Marvin also had a dramatically improved flex-wheel intake, which eventually became the intake of choice among teams. We also made the catapult faster (however, from that point on, we made the decision to only use the catapult in skills runs, where there was no opponent). Finally, because we moved motors from the climber to the drivetrain, we redesigned our climbing mechanism to be a fast and effective pneumatic hang. We maintained the same wings, as they were super effective in pushing around triballs, but added a second air tank to accommodate the climb. It was with Marvin that we won a tournament for the first (and, unfortunately, last) time.

In the weeks preceding the world championship, as the team reviewed previous matches to finalize the robot design for the final complete rebuild, we noticed a slight shift in strategy yet once more. The best teams began to prioritize a few key elements while removing resources from other components. Specifically, super fast yet high-torque drivetrains became prevalent, a focus was put on optimizing the intake, and a few teams had two sets of wings (each with different designs) for use in particular tasks. Using this information, we built our final bot of the Over Under season, Luna. Luna had a powerful drivetrain, containing the vast majority of our robot’s motors as well as a carefully chosen gear ratio. Luna’s intake was one of the biggest areas of change, though. Through participating in numerous scrimmages (mock tournaments) and reviewing our gameplay, we slowly fine-tuned the flex wheel intake to match the ideal strategy. Thus was created an intake which could effectively intake, outtake, matchload, and score, all within half a second. We added two sets of wings and improved our climb mech using newly available pistons. Also, we made the catapult detachable (since we weren’t planning to use it in matches) and lowered the robot’s center of mass to avoid getting tipped. Luna was the best and final iteration of 315P’s robot, and the design we took to the world championships.

The Competitions

We went to numerous tournaments and learned a huge amount from each. Here’s a run-down of the key competitions the team had over the season.

- We took Friday to a small, middle school-only tournament in Granite Bay, California during November ’23. There, we made it to the finals and learned a lot about game strategy.

- Our next major event was at the University of California, Berkeley. This was a massive tournament with over one hundred teams from both the middle and high school divisions. We didn’t fare well, and failed to make it to the elimination rounds. However, it was at Berkeley that the team took ideas from the strategies/designs of some of the best high school teams in the world. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to attend Berkeley :(

- We took a looooooooong winter break to allow for some vacationing and completely revamp our strategy. It was then that we shifted our top priority from just getting practice into qualifying to the regional championship (which we referred to as states, since it had an equivalent purpose as a state championship). States was the next event through which we could qualify to the world championship, and thus we began devotedly attending every local tournament in a feverish hope to qualify.

- We started off by attending two tournaments at the local India Community Center (ICC). They were medium tournaments (around 40-60 teams); because they were combined (high school + middle school) tournaments, the team mostly treated them as practice and opportunities for scouting (that is, identifying possible alliance partners for the state championships). We didn’t do relatively well at either of them.

- After taking notes on so many other teams’ gameplay and robot designs, we finally felt it was the right time. We spent about a week building and familiarizing ourselves with Marvin, with the changes listed above.

- Next, we went to a Sacramento tournament. This one was a medium-sized one that was middle school-only. With a much more level playing field, we gave it our all and received a just result. We won the tournament, having allianced with the same team which we’d finalized with. This qualified us for the state championships.

- The final major tournament we attended before the state championship was a massive middle-school event, about the same size as Berkeley. We didn’t perform that well, and thus began overhauling our robot starting the very next day.

- Our team realized that the most important way we were going to qualify to the world championships is through skills, and began a long path to improve our skills score by over one hundred points. We improved the catapult, the autonomous code, and the driver strategy; rewrote the driver controls to make them more intuitive; practiced our match loading and wrote specialized code to support it. This all paid off…

- …at the state championship. In matches, we did okay, getting to quarterfinals. In skills, though, we got to second place; since the first place in skills (that is, the skills champion) had already qualified to worlds, we received the qualification that they would have gotten for skills champion. We had, just barely, qualified for the world championship.

The World Championship

In a blink of an eye, we were loading the robot onto a plane to Dallas for the world championships. We’d spent hundreds of hours at this point on our final rebuild of the robot, Luna. Luna was a robot that combined all of our previous learnings about robot design into a beast: lightweight, powerful, and efficient. We attended every scrimmage that Paradigm had to offer, playing against our sibling teams in a bid to learn from each other. And, finally, we spent just as much time obsessing over the hundreds of lines of software and the complex game strategy.

Quick summary of how the world championship worked: about 480 teams attended worlds, which was a 3-day event. We were split into 6 divisions with about 80 teams each. Each division functioned as their own tournament, with independent awards, rankings, etc. The winners of each division would progress into the sports-stadium-like Dome, where they’d compete to crown the world champion.

We had a simple strategy. It could be summarized into one word: win. During qualifications, which comprised the vast majority of worlds, our single goal was to have the #1 ranking. Our ranking was based on two main factors: winning matches, and the Autonomous Win Point (AWP, which the robot could earn by completing a set of tasks during the autonomous period). The coach assigned me a single role: getting that autonomous win point.

Qualifications were just absolute mayhem. I was the first person to talk with each of our alliances. For every single match, I’d have to drag out our future alliances into the practice field to test their autonomous programs and compare against ours. This would take about ten minutes; I would then spend anywhere from 5 to 40 more minutes fine-tuning our programs. I would then wheel the robot along with a dozen pounds of support equipment all the way back to our team pit. During matches, I had a less important, yet still vital role: communicating with our alliance to ensure everyone collaborated effectively. After matches, I’d go back to the pit, help my teammates fix and improve the robot, and then pore over footage of our alliance’s and opponent’s matches to determine their game and autonomous strategy. Then, I’d find our future alliance to discuss strategy with. And thus the cycle would start all over again. We ended qualifications ranked fifth out of the 80-some teams, having won 9 out of our 10 matches.

Eliminations were fun, albeit our performance left a bit to be desired. We allianced with one of our sibling teams, 3177B. (I know, they don’t have a 315 team number, but Paradigm considers them to be a member.) Again, I spent another half-hour coordinating autonomous and game strategy with them. By now, I was utterly exhausted, and elimination games offered me some rest. We lost in the quarterfinals, but I am still really happy with how we did. We performed to the best of our ability, and for a team with two rookie members (that is, team members who are competing in their first year of V5RC), I was honestly pretty surprised with that degree of ability. An added bonus was that our team received the Amaze award, which was the highest award in our division. This judged-award represented our team’s admirable conduct in matches, skills, interviews, and engineering notebook submissions.

The world championships were, of course, the highlight of the trip, but I want to take a moment to appreciate the magnificent city of Dallas. The Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center, where the championships were held, is massive, and deserving to be a city of its own. (No wonder I walked more than 20,000 steps every day!) After getting the awards, the team headed to the dome (also part of the convention center) to watch the world finals. We were delighted to see a team we knew well from our region (1698Y) make it to the world finals, and the following reveal of the next game for V5RC only added to the experience. My dad and I even took one day after worlds to just go sightseeing around Dallas: from the Tex-Mex cuisine to the John F. Kennedy memorial museum to the Reunion Tower to a giant eyeball(?), there were so many amazing sights. The trip to Dallas was definitely worth it.

Conclusion

I would definitely recommend trying out V5RC or an equivalent competitive robotics program. Over the course of the season, I made new friends, learned life skills, and found out the difference between aluminum and steel screws. It was an overall enlightening experience, and one that I’m excited to continue next season.

Note from 2025: this ends my blog post

Season 2: High Stakes

Luckily for whoever is still reading this, there are no more cringe blog posts for you read 🥳

After we had finished celebrating our awards, we began working on our robot for the next season, High Stakes. I won’t bother going through the game or the evolution of our robot again, but for reference, here is a description of the game. I’m not going to write a sonnet about my time on the team again, but I’d instead like to dive a little more into some technical details in this section. I’ll go in order from the bare metal to the code I wrote.

Kernel

Any and all code I write for the robot runs on the VEX V5 brain:

This runs VEXos, which is not a full-fledged operating system, per se, but enables the execution of custom binaries which can interface with I/O. I/O on the V5 brain includes quite a few things, most of which come from either the screen, the smart ports (pictured above on either vertical side of the screen), or the three-wire ports (not shown above).

This runs VEXos, which is not a full-fledged operating system, per se, but enables the execution of custom binaries which can interface with I/O. I/O on the V5 brain includes quite a few things, most of which come from either the screen, the smart ports (pictured above on either vertical side of the screen), or the three-wire ports (not shown above).

- Inputs

- Touch events on the brain screen

- Sensing inputs from any smart ports (including motor readings)

- Sensing inputs from any three-wire ports

- Battery levels

- Reading files from the SD slot

- Serial over the USB port

- Outputs

- Displaying things on the brain screen

- Actuators (mostly motors)

- Pneumatics over three-wire ports

- Writing files onto the SD slot

- Serial over the USB port

Typically, these binaries are built and uploaded through VEX’s proprietary IDE, VEXcode, or its corresponding VScode extension. However, there is also a division of VRC called VEXU, which is a collegiate-level version of the competition with more coding, two robots per team, and a few other different things. It turns out that Purdue University has a VEXU team, BLRS the Purdue ACM SIGBots (one of my all-time favorite teams :D), and clearly college students have too much time because they wrote their own operating system for the V5…

PROS

PROS (either Purdue Robotics Operating System, or the infamously recursive PROS Robotics Operating System) is a custom RTOS built on top of the V5’s VEXos kernel by the Purdue Sigbots team. It looks something like this:

- You write C++ code that calls PROS APIs

- PROS uses a custom build tool to build it into a binary that accesses the correct I/O on the V5

- You upload the binary (or a differential patch to the binary) to the V5, which then runs it using its kernel

- Voila! Your robot does things

“Wait but this is just what VEXcode does 🤓”… yes, that is true. However, PROS is chosen by the top teams for a number of reasons:

- Documentation. PROS has actually well-documented APIs compared to the mess of VEX APIs. For example, VEX only somewhat documented their APIs a few months ago — even though they’ve existed for years!

- External libraries. VEXcode’s tough integration with other tools makes it hard to have a proper package management system. In contrast, PROS has a robust library ecosystem with hundreds if not more packages ready to install via their CLI (another thing that VEXcode doesn’t have).

- IDE integration. While PROS has a recommended VSCode plugin, its extensible CLI means you can code in it from everywhere (including Zed, my favorite code editor). VEXcode can only be used from their proprietary app or VSCode extension. Also, VEXcode has very weird code structure, while PROS’ is just regular C++ with cpp and header files.

- PROS is open-source! All of VEXCode’s APIs and protocols are closed-source (although the SIGbots team got access to it under a NDA to develop PROS) while every single bit of PROS is open-source and on Github. This has enabled the community to do a bunch of cool things. The coolest of these, in my opinion, is vexide, which is a runtime like PROS for the V5, with two major differences. 1) It supports async. But wait, C++ doesn’t have async. And then we have 2) It’s written in Rust!

This is hopefully enough to convice anyone to switch to PROS! Time to go one abstraction level higher.

VOSS

VOSS is a PROS library which includes utilities for robots. It contains quite a few utilities:

- Motion, including custom path planning, PID, motion controllers, etc.

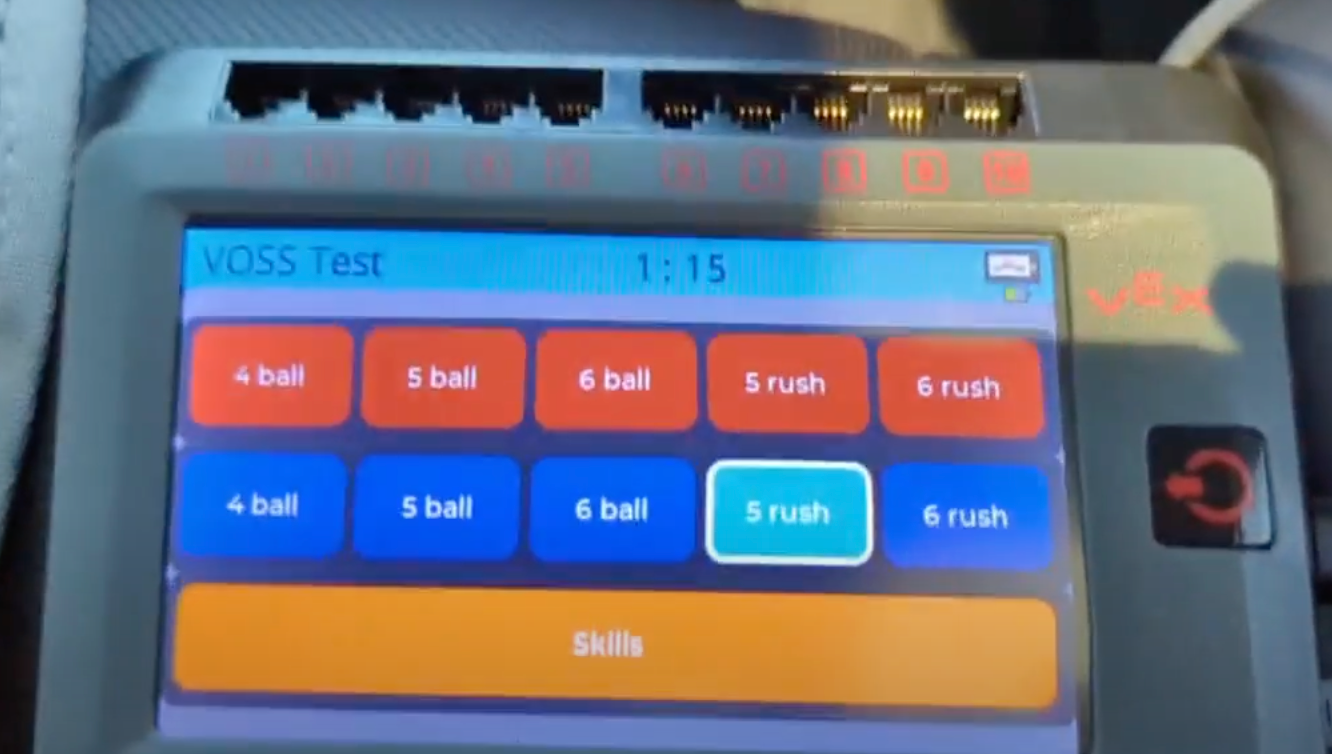

- An autonomous routine selector (wait a little bit more to learn what that means!)

- Odometry. This is basically some math that takes in sensor readings (namely, from inertial movement units and unpowered tracking wheels) and does trigonometry to determine the robot’s position and orientation.

Each of these things on its own isn’t super hard, but VOSS packages them all neatly into one, well, package. There are other libraries in this space, like LemLib, but I chose VOSS for our codebase because 1) it supported the newest PROS version (4.0), 2) it was written by Purdue SIGbots, who also maintained PROS, and 3) it had an intuitive and well-structured API that put my code to shame. VOSS is truly magic; it replaces about two hundred lines of odometry code, followed by dozens of lines of path planning math, followed by another hundred lines of PID controls, with this:

chassis.move({1.0, 1.0, 30}, 100, voss::Flags::RELATIVE);It’s honestly insane how much thought the SIGbots team put into this, so please give them a ⭐ on Github :)

My code

All of the above work is either of VEX or the SIGbots, so it’s finally time to dive into my code! All of the code I’m talking about is from this repo. My code is honestly very simple, less than 500 lines, so this overview ought to be pretty short.

Level 1: Wrappers

VOSS provides an excellent API surface to build off of, but at the time of writing the initial codebase, the team was considering adding another coder, and to simplify their onboarding, I decided to write yet another wrapper over VOSS which abstracts even more away. Namely, it handles the motor setup, odometry parameters, etc., and limits the number of functions that could be called (as a means of enforcing that other coders wrote appropriate code). Here is a basic header containing basically the entire wrapper API:

// before this, there are about 50-100 `#define`s which store the config parameters for all of our code.

// all `#include` or `use` calls are omitted

// [a number of internal functions]

namespace robot {

void rumble(const char* sequence);

void log(std::string message, std::string end = "\n");

void log_pose(std::string end = "\n");

enum class Direction;

extern pros::Controller controller;

}

namespace robot::selector {

void init(std::map<std::string, void(*)()> game_autons, VoidFn skills_auton, int default_auton, bool show_graphics = true);

void run_auton();

}

namespace robot::auton {

void start(voss::Pose starting_pose);

void checkpoint(std::optional<std::string> point = std::nullopt);

void end();

}

namespace robot::drive {

extern bool mirrored; // false = red

void init();

void face(double angle, double speed = 100);

void go(double distance, float speed = 100);

void swing(double angle, bool reversed = false);

void set_mirroring(bool state);

void set_position(voss::Pose position);

}

namespace robot::subsys {

void init();

extern Direction intake_state;

void intake(Direction direction, float speed = 1);

void wsm(Direction direction, float speed = 1);

}This is quite the shortening from the ~100 public functions that could be called from VOSS. If I wanted to execute a particularly customized motion in a routine, however, I would directly call a VOSS function. A briefly explanation of what each namespace contains:

robot— the root namespace- A number of logging functions (including

rumble, which vibrates the controller according to a specific pattern) selector— the autonomous selector- Initialize the selector with a

mapmatching various routine names to their corresponding functions run_autonwhich ran the selected routine

- Initialize the selector with a

drive— the chassis codeset_mirroring— sets the mirroring of the drivetrain, this will be explained more later- The others are fairly self-explanatory, just a collection of simple functions to move the robot around

subsys— code for controlling other systems on the robot * Functions for changing the state of other subsystems

- A number of logging functions (including

Now that this is all out of the way, let’s explain a bit more about the autonomous selector.

Level 2: The autonomous selector and autonomous routines

As noted in the first blog post, V5RC matches start with a 15-second autonomous period. This is where the code I write gets executed (there are only ~50 LOC dedicated to running in the driver control period). Strategy in High Stakes is very important; for example, if teams do not coordinate their autonomous strategies, both robots could try to score on their alliance stake at the same time and clash, preventing either one from scoring and messing up the rest of the autonomous routines. Thus, a number of different routines, colloquially known as “autons”, are needed. There is, of course, also a need to choose two things at the beginning of a match: which auton to run, and what side the robot is on (blue or red). The latter is important because in High Stakes, the field is symmetric by reflection (while the Over Under field was symmetric by rotation), creating the need to “mirror” the turns of an autonomous routine if it switches sides. This was handled by our selector, which ended up looking like this:

(ignore the thing at the bottom that says “Skills”.)

(ignore the thing at the bottom that says “Skills”.)

When the field control told the robot to run its autonomous, whichever routine had last been clicked on was run. The code for autons themselves look something like this:

// code/src/autons.cpp

#include "pros/rtos.hpp"

#include "robot/basics.hpp"

#include "robot/robot.hpp"

using namespace robot;

using namespace robot::drive;

using namespace robot::subsys;

using namespace voss;

// ...

namespace autons::shared {

/**

* @brief An auton whose only goal is to gain the Autonomous Win Point (AWP).

*

* @note This auton was designed with intake raise and odom.

*

* @details

* Starting position: NR starting position

* 1. Aligns with alliance wall stake & scores preload

* 2. Gets mogo

* 3. Get NR square rings

* 4. Touch ladder

// */

void awp() {

auton::start({0,0,180}); // UTB mirrored ? 0 : 180 ; please test auto mirroring

/**

* Align with alliance wall stake & score preload

*/

go(-16);

face(90);

go(-9);

go(-2);

go(1.75);

intake(Direction::FORWARD);

pros::delay(550);

/**

* Get mogo

*/

go(10);

face(-49);

mogo.extend();

go(-27);

intake(Direction::STOP);

go(-10, 30);

mogo.retract();

pros::delay(800);

auton::checkpoint("Got mogo");

/**

* Get NR square ring

*/

face(139);

intake(Direction::FORWARD);

go(17.5);

pros::delay(400);

/**

* Get ring from stack next to square

*/

swing(-32, true);

go(20);

pros::delay(400);

auton::checkpoint("Got da goods");

/**

* Touch ladder

*/

go(-25);

go(-5, 60);

auton::checkpoint("Touched ladder");

auton::end();

}}

// ...That’s basically all I have to say about the robot’s codebase. Hope some of these details were helpful!

Epilogue

Due to internal frustrations with how the team was being managed and the lack of focus on coding, I left the team in October 2024. As for the future of the team, they recently qualified to the World Championships by getting a design award at states. Unfortunately, their coding is in limbo at the moment as multiple other coders have left the team or are busy with other extracurriculars. As noted above, to preserve my original code (entirely written by me, with no external authors), I have cloned the repository at the time of my leaving the team in this MIT-licensed repo. Hope this post was helpful/inspiring/something!